Six years ago Gocha, now 27, from Tbilisi, Georgia tested positive for HIV. The same year, the Orthodox church and the far-right “aggressively ambushed” a small rally that he helped to organize, held to mark the international day against homophobia and transphobia.

Now, in 2019, Tbilisi has just held its first Pride event and Gocha’s organization, Pomegranate, is encouraging and supporting more LGBTQ+ people to find out their HIV status and demand treatment. Gocha shares his perspective on how right-wing views on gender and sexuality and barriers to HIV treatment interlink in Georgia, and how access to optimal treatment needs to improve for everyone.

Interviewed by Gemma Taylor.

Gocha poses at ballroom, a new LGBTQ+ friendly café-bar and safe space in the city, named after Ballroom culture. © Gemma Taylor/Make Medicines Affordable

An estimated 11,000 people are living with HIV in Georgia, the prevalence rate is higher among men, and civil society groups, such as Pomegranate, believe it is higher among LGBTQ+ people. “This is because of a double-stigma,” explains Gocha. “It’s difficult to be ‘different’ in Georgia. We have strict rules, or gender roles, about how men and women should behave. When you don’t match up with this it is common to be victimised.”

A lack of LGBTQ+ specific services and a fear of being mistreated prevent people from accessing prevention and treatment services. Let’s be clear, the only reason there are higher rates of HIV among LGBTQ+ people is because of a stigmatising, debilitating environment.

Dr. Maia Butshashvili, based in Tbilisi, agrees with Gocha. “Late detection is our biggest problem. HIV deaths have been increasing recently because of it. The people hardest to reach is also where the epidemic is concentrated, among men who have sex with men (MSM). With MSM the outreach is not as good as it should be.”

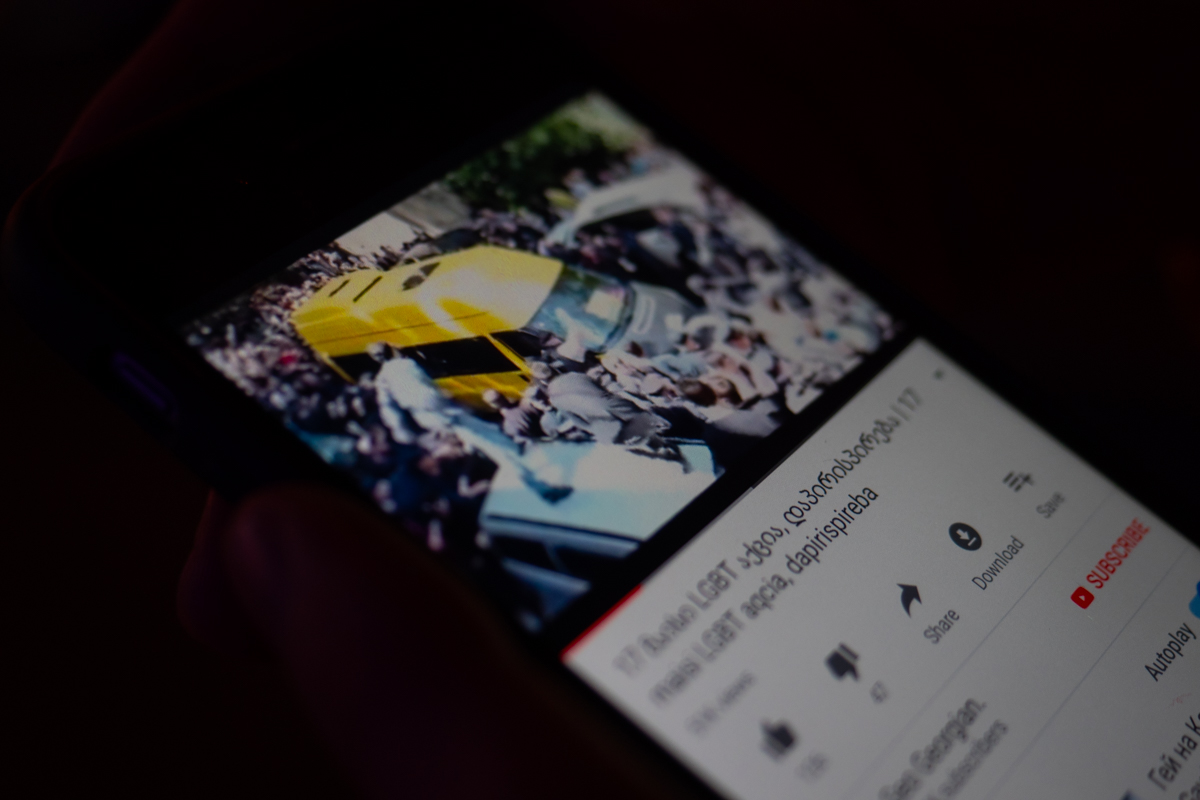

The ambushed rally in 2013 is an indicator of the level of stigma directed at LGBTQ+ people. “It is very hard for me to remember that day”, says Gocha, showing videos of the homophobic-fuelled attack on his phone. “It was organized by the orthodox church. There were 20 or 30 thousand people attacking us versus just 15 or 20 of us the bus, it was horrendous”.

“It is very hard for me to remember that day”, says Gocha. “There were 20 or 30 thousand people attacking us versus just 15 or 20 of us on the bus, it was horrendous.” © Gemma Taylor/Make Medicines Affordable

“Only a few LGBTQ+ people or people living with HIV have the courage to talk about protecting our rights. We can’t move forward and solve some really important issues unless we do.”

When Gocha tested for HIV he was already an LGBTQ+ support worker. “I was encouraging other people to test, so I tested myself, and my result was positive. I started treatment straightaway and the virus was undetectable within six months, and still is now.”

Gocha had good social support but one of the reasons he is so driven is because he sees the challenges being faced by others. “When I look to back to when I was diagnosed, I’d say it’s more problematic with stigma now and there’s still not enough services.”

Un-targeted treatment

Once an LGBTQ+ person has got over the hurdle of testing, unfortunately there are more barriers to face.

“There are no services targeted at specific groups, everyone has to go to one big center to access treatment,” explains Gocha.

In addition to the same issues that everyone living HIV faces, such as finding the time or money to travel, LGBTQ+ people and other ‘key populations’ have additional challenges. “For example, a transgender woman would have to dress like a man to go the center, so she may not access services at all, gay men can’t be open about their sexuality so asking questions about getting the right treatment, such as PREP can be difficult, and the building closes early in the day, which is a problem for sex workers and other people who work late nights.”

Tbilisi celebrated its first Pride in 2019. @TbilisiPride

Loaded questions

Once someone is on treatment, they are bound to have questions, such as if there are potential side-effects, or whether the treatment prescribed is the best one for them. These typical concerns can be difficult to allay.

Gocha has witnessed a low level of treatment literacy among both people living with HIV and practitioners. “If you don’t know the question to ask how can you ask it?” says Gocha. “Not only that, but if you do ask a question, all too often the health professionals don’t have the answer anyway.”

“I am on a dolutegravir (DTG) based combination,” shares Gocha. “I’ve been on the treatment for about 18 months. It’s better for me because it is just one pill a day, and should have less side-effects.”

That wasn’t why Gocha changed his treatment regimen though. Instead it was simply because “they ran out of the medicine I was on”. When he asked about why it had changed, were there any side-effects, etcetera, he recalls how: “The nurses were quite angry, they wanted to know why I had so many questions – about my own health! They told me if I thought it was a problem, then not to come here to get it any more.”

Gocha has sympathy for health workers, he believes they are under-paid and over-worked. However, HIV treatment can only be prescribed and collected from National AIDS Centers in Georgia, it is not available via local surgeries. “If you don’t like how they are serving you can’t just go and find somewhere else like you would with a café!”

“I have had to become my own doctor, my own health advisor.”

Gocha accesses an app called AIDS info. “It’s a drug database which tells me the contraindications of the different drugs. It’s a very useful app, but it’s in English [and Spanish], so it’s difficult to access for many people.” The knowledge Gocha gains, he is able to pass on via Pomegranate’s network.

Gocha, a co-founder and director of Pomegranate pictured with friend, Tengo. Tbilisi, Georgia. © Gemma Taylor/Make Medicines Affordable

He knows that his current DTG-based regimen is considered a more optimal treatment than his previous therapy, but tailored options need to be on the table. His friend Tengo has recently been prescribed the same drug. Initially, he too had only taken because there was a stock-out of his regular medicine but then found that his side-effects (migraines, dizziness and sleeping problems) stopped. “I had to battle with the doctor to stay on it as he was saying it was for second- and third-line only,” says Tengo.

In June 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommended that all countries immediately adopt DTG-based regimens as the preferred first-line treatment for HIV.

The price of living with HIV

In theory everyone living with HIV is entitled to free treatment under Georgia’s Universal Health Coverage (UHC) scheme.

However, over-patenting and over-pricing means that there are concerns about the affordability of this. While the aim is to test and treat everyone, the reality is that current budget is struggling even with less than half of people on treatment. Currently the country is receiving financial support from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB And Malaria (the Global Fund), but this support is transitioning out. With it comes the fear that the challenge of achieving universal access will become even more pronounced, and in current stigmatizing context LGBTQ+ people may be worst affected.

Connecting matters

Civil society is working hard to fill in the gaps and work towards a more sustainable and inclusive system for health and rights. Gocha is a co-founder and director of Pomegranate which established in 2018.

“We’ve called our organization Pomegranate because it represents all the different parts coming together as one. There is the blood of the pomegranate connecting all the expert civil society groups, including sex workers, LGBTQ+ people, drug users, and people living with HIV.”

“We’ve called our organization Pomegranate because it represents all the different parts coming together as one. ” Paintings at a market in Tbilisi. © Gemma Taylor/Make Medicines Affordable

Pomegranate will work with our campaign partner in Georgia, the Open Society Georgia Foundation (OSGF), to provide prevention services, psychosocial support and advice and advocacy on treatment and rights.

You can read more about OSGF’s priorities here, which includes strengthening community and civil society organizations, increasing treatment literacy, reducing prices and ensuring HIV treatment is sustainable.