“I was in prison when I was diagnosed with Hepatitis B,” says Temo, 33. “I was just left with the news with no information.” Temo is living with both Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C. He has treatment for one virus but not the other. His dual diagnosis also requires a dual response – tackling the overly punitive laws on drug use and making medicines affordable.

Interview by Gemma Taylor.

Temo’s first thoughts when was he was diagnosed with Hepatitis B were for both for himself and for others. “I was in jail and isolated. I didn’t know what the virus was or what it meant for me. I had poor mental health and no support. I also thought the jail was a dangerous place to pass on the virus, I was fearful of being contagious.”

That was eight years ago. A year ago, Temo also tested positive for Hepatitis C. His thought process was similar, but this time he had support, and the person he was worried about passing the virus onto was his wife, Mariam, 27.

Mariam always saw the person not the ‘drug user’. The couple live with Temo’s family. © Gemma Taylor/Make Medicines Affordable

Mariam always saw the person not the ‘drug user’. “I was working in a bar when we met. He told me the first time we talked that he used drugs. He told me so simply and easily. It’s not a big deal for me, for us. As we got to know each other, I decided to make our relationship deeper.”

They’ve been together for two years. Do you have children? “Not yet,” Mariam smiles. The couple live with Temo’s mum and siblings while they save for their own place. The only ‘little-one’ they’re focused on for now is Mr. Archibald, their kitten.

Friends pop in and out of the apartment, it’s a very inviting, warm home. Unfortunately for Temo, as a drug user, even though he’s now on opioid substitution therapy (OST), the same hospitality is not extended to him or his peers out on the street.

The same hospitality that Temo offers to friends and his community is not extended to him or his peers out on the street. © Gemma Taylor/Make Medicines Affordable

Police microscope

“I usually go out with Mariam, especially if it’s a late night. The police are less likely to stop you if are with a woman.” Temo explains: “The Georgian law states that even if you are found with just a particle of a banned substance you can go to jail for 6 years or more. People are being prosecuted for possessing microscopic amounts of drugs.”

“I’ve been prosecuted for drug use several times. I’ve been in prison, I’ve been on probation, and fined on other occasions. The time I was imprisoned, I paid 10,000 lari (approximately $3,500 USD) to be released early after six months.” This was following a change in president, after which an amnesty followed.

Chaos. In one year the police stopped 50,000 people for on-the-spot drug checking. © Gemma Taylor/Make Medicines Affordable

The fear of arrest hasn’t gone away though. “There’s lots of drug spot-checking on the street, just ‘on suspicion’,” says Temo. “They like to stop the ‘skinny ones’,” says Mariam. Temo explains how in one year the police stopped 50,000 people for drug checking. “If a urine sample tests positive you could be sentenced. It meant people were being sentenced even if they’d smoked weed a month ago.”

“In 2014 I was taken to the station along with some activist friends. We used article 42 of the Constitution of Georgia to resist. The law states that you can’t give someone a biological sample which will work against you. Our refusal set a precedent – and after this thousands of people used the law like in this way. The practice has been officially changed but some people don’t know, and so it still get used unofficially.”

The treatment ‘for all’ is NOT reaching everyone

“I started treatment for Hep C two weeks ago,” says Temo. It’s too early to say if he’s feeling any different, but he can hope to be cured in around 12 weeks.

The drugs that can offer a cure is sofosbuvir-based treatment which is being provided free to Georgia from Gilead in a ‘Hep C elimination’ scheme. Roughly 50,000 people in the country that have accessed treatment, only around a third of people living with the virus. However, issues remain – particularly around access and also the sustainability of ‘goodwill’, tax-deductible donations.

Temo believes Georgia’s overly punitive drug laws are a key factor for the low take-up rate, with two-thirds of people still in need of Hep C treatment. “On one hand the government says ‘we’re going to help, we have a Hep C elimination program’ but on the other hand they make it difficult for you, by continuing to criminalise drug users, a key group who need the treatment. People are essentially hiding from the government – and risking their lives.” Temo has supported people to access treatment, including Mariam’s father.

“I know people who died before they could get to start the programme. Friends of mine lost their lives. Too many.”

Whole person, half the treatment

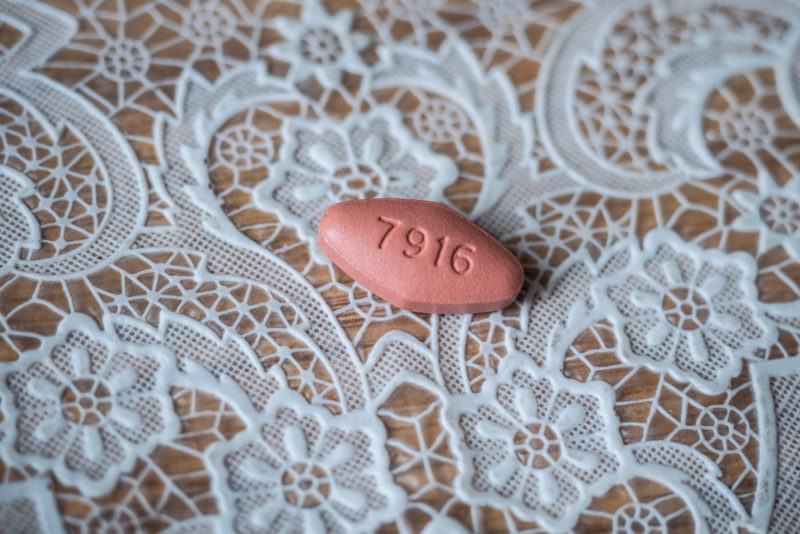

The irony for Temo is that, “I could be cured of Hep C but still have Hep B. It’s really frustrating. I’m not being treated as a whole person.”

Temo is living with both Hep B and Hep C. He has treatment for one virus but not the other. © Gemma Taylor/Make Medicines Affordable

“I can’t afford to start treatment for Hep B. It’s 300 lari per month (approx $110), and once you start you can’t stop, otherwise you may build up resistance. So to begin treatment you have to know that you can pay this every month forever.”

“I am ‘chronically affected’. This means I am among the 15% of people for who the virus will not self-cure and so treatment is essential.”

For Temo, and others in his position, this means dealing with side-effects which can include extreme fatigue, nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain. The more serious, life-threatening risk is of developing liver cirrhosis or cancer. Being cured of Hep C does not eliminate this risk for Temo.

We want better pricing, not ‘benefactors’

Make Medicines Affordable’s partner in Georgia, Open Society Georgia Foundation (OSGF) wants to see a sustainable response to all diseases, so Temo and others can be treated as a whole person.

“While it’s good news for the third of people in need who have accessed Hep C treatment, we need to see this addressed systematically through lower prices and a patent system that prioritizes public health over profits. It is not sustainable for pharmaceutical companies to act as a ‘benefactor’ on isolated treatment. It does not solve the underlying need for fairer, affordable pricing of all drugs,” says Marina Chokheli, Public Health Program Coordinator.

“The price of drugs, particularly patented drugs from originator companies, poses a serious challenge for Georgia’s Ministry of Health. If sustainable price reductions are not achieved, universal access across a range of diseases will not be within budget.”

Fair pricing = choices

“You should have choices, right?” asks Dr. Maia Butshashvili, who would like the option to prescribe entacavir for Hep B. Entacavir is patented in Georgia until 2021. One year of treatment, per person, can fetch the company, Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS), $9,600 (USD). “Right now, we’re stuck on one treatment. It’s not bad, but different patients need different options, plus when there is competition it also reduces price.”

“There is no state program for Hep B, treatment is lifelong, and insurance companies won’t pay a penny. It’s very hard for patients to pay out of their own pocket – plus the cost of lab tests that are needed every 3-6 months, so only a small proportion of patients can afford it.”

“I have a lot of patients who can’t even afford to pay for the tests. So we know they have Hep B, but we don’t know anything about their viral load or liver status. It is very frustrating.”

“We’ve had a sad situation of a few mortality cases with Hep B. Since 2000 there has been a government vaccination scheme, so it’s largely over 18s getting infected as they weren’t vaccinated.”

“Right now, we’re stuck on one treatment. It’s not bad, but different patients need different options, plus when there is competition it also reduces price,” Dr. Maia Butshashvili. © Gemma Taylor/Make Medicines Affordable

“I’m not hiding”

“We need an affordable Hep B and Hep C programme for the long-term. Community and patients have to sit together with government and pharmaceutical companies to find ways to access more affordable treatment,” says Temo.

“The attitudes, policies and politics surrounding drug use made me want to be an activist and engage in this sort of work. I’ve been using drugs since 21 and an activist since 27.”

Temo is a member of the Eurasian Harm Reduction Association (EHRA), and he has established a NGO with friends. “It’s for young people – millennials. We’re still deciding on a name.”

Temo has five years’ experience in harm reduction, peer outreach and advocacy. “For me, advocacy on drug policy is the most important element, including the street protests, which paved the way to make a difference by demonstrating public support.”

Advocacy work carried out by Temo, OSGF and allies is changing attitudes. “Stigma is still there of course, people think a drug user is a criminal, someone who might steal stuff from their house, but it’s easier to be public. I can say I’m a drug user during TV interviews and face less problems than I would have done, say, five years ago.”

Having seen change, Temo is optimistic that more positive change will come. “It would be one thing if the drugs didn’t exist to save and improve people’s lives, but they do, so we must find a way.”

“I hope one day the government will treat everyone. I’d like to be able to protect our future child.”

Mr. Archibald, Temo & Mariam’s kitten. They’re saving for their own place and planning to have a child in the future. © Gemma Taylor/Make Medicines Affordable